|

LETTERS

FROM PATIENTS

|

|

NARRATIVE IN PROGRESS

|

|

The following is very much a work in progress as

I reflect on my life and the times during which I

practiced neurosurgery both as a civilian and as

an officer in the United States Armed Forces. This

text is a rough draft that will be often revised

until I am satisfied that the finished narrative

is the best I can produce. Many of the graphics

are heart-wrenching and horrible to behold, but

they are pictures of some of the best young men of

that generation. Looking back decades later the figures of troops

in country and numbers killed illustrated our

presence through the years during our

nation's involvement: SOURCE: Dept of

Defense Manpower Data Center End of Year

U.S. Troops in South

Vietnam

Total Killed to Date 1959

760

-

The total number of U.S. military members killed

in The International Armed Conflict in Vietnam At the time of the dedication of The

Vietnam Veterans Memorial Wall in 1982

only 57,939 names appeared.

The project began despite opposition from General

Westmoreland and other army officers. The

principal purpose of this "McNamara Line" was to

sound the alarm when the enemy crossed the

barrier. Allied firepower in the form of air and

artillery strikes would rain down upon the

People's Army of Vietnam (the North Vietnamese

Army) in order to curb penetration from the north.

This McNamara Line was an attempt to merge modern

technology with one of the oldest defensive

techniques in warfare. The United States would

unfortunately learn that more than sophisticated

technology was necessary to make an effective

barrier. The project was begun, but it turned out

to be impractical and was eventually discontinued. The conflict was escalating, and with the increase in hostilities there was an increase in casualties. In 1965 there was only one army hospital in Japan and that facility at Camp Zama had 100 available beds. By 1966 there were four hospitals, including the 7th Field Hospital (400 beds), the 249th General Hospital (1,000 beds), and the 106th General Hospital (1,000 beds). The U.S. Army Hospital at Camp Zama had increased the number of its beds from the original 100 to 700. It was in the summer of 1967 that I drove to San Antonio, Texas for an introduction to the military and basic training at the Medical Field Service School and Brooke Army Medical Center before assuming responsibilities for the neurosurgical care of soldiers wounded in what was called the International Armed Conflict in Vietnam.

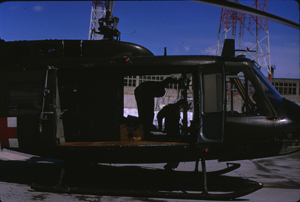

The view of Fort Sam Houston as we approached in

a helicopter while transporting a severely wounded

soldier from the 249th General Hospital later in

my tour of duty. We learned that the conflict in Vietnam had brought about significant changes in military medicine since our nation's most recent extended fighting in Korea. Two major improvements were in aero medical evacuation and in the mobility of well-staffed and well-equipped hospital facilities. Combat medical support had to be modified in this region where the battlefront was ill defined and the guerilla tactics of the Viet Cong gave the enemy the opportunity to strike deep within areas once thought to be well under our control. The UH-l (Huey) helicopter could transport as many as six to nine patients at one time. Most patients could be evacuated within 30 to 35 minutes of wounding and the skill and competency of the medics both on the ground and in flight resulted in salvaging the lives of many soldiers who would not have survived in earlier conflicts. Before our involvement in Vietnam came to an end 7,013 Hueys had been deployed in country. 3,305 were destroyed, 1,074 pilots were killed along with 1,103 other crew members. A second major change was to be in the deployment

of the MUST (Mobile Unit Self-Contained

Transportable) structures that had been developed

to replace the MASH (Mobile Army Surgical

Hospital) units of the Korean conflict. The following are pictures of various MUST

components:

Individual containers before assembly

An expandable shelter in place

A utility module Central Material Supply with autoclave

X-ray room

Laboratory The first MUST hospital to arrive in Vietnam had been the 45th Surgical Hospital that was set up in Tay Ninh in October, 1966. Its commander, Major Gary Wratton, MC, was killed in a mortar attack before the unit began functioning in early November. In time a total of six MUST hospitals was established in Vietnam. I had brought along my copy of the NATO Handbook

“Emergency War Surgery” that I planned to study

before turning in each night. My only extended personal interaction with a single individual during the month-long introduction to the army was an interview regarding my future in the military. The interviewing officer explained the advantages of extending my term of service from two to three years. He assured me that this would make my posting to Vietnam much less likely. I could have an assignment at one of the major army hospitals outside the theater of operations in Southeast Asia. I didn’t bite. I had no doubt that the needs of the service would determine where I might be stationed during the three years. My interviewer couldn’t convince me that the three years in a non-hostile setting could be guaranteed. I opted to let the army send me where it wished, but I wanted my two-year obligation to be the total of my service time. I had read enough about the current conflict to know that the sooner I returned to civilian life the happier I’d be. There was a two-week interval after Fort Sam Houston before my flight from the West Coast to my assignment in Japan. I returned to Massachusetts to make arrangements for the army to ship family items overseas and to rent our house to a colleague who was emigrating from the United Kingdom to practice medicine in Boston. I had left the family station wagon in San Antonio and it would be sent overseas in time to arrive in Japan about the same time as I. Two of my four children were in elementary school and I explained to them the advantages of living overseas for two years, and the great opportunities that we would have contrasted with two years in our Boston suburb. In any event it was certainly preferable for all of us to be together rather than separated for these years. Transportation for my wife and four children was arranged. They would join me in Japan after I had arranged for housing and schooling for the two older children. In late August I flew to the west coast and stayed with a fellow medical draftee and his family in San Francisco before boarding a chartered flight at Travis Air Force Base midway between San Francisco and Sacramento. We flew to Tokyo with a refueling stop at Elmendorf Air Base in Alaska. I arrived in Japan in mid-September and my family joined me in mid-October.These are a few photos taken on the hospital grounds soon after my reporting for duty:

The 249th General Hospital was located northwest

of Tokyo in Asaka prefecture. This unit was among

the nearest complete hospital centers for army

casualties in South Vietnam. We were 2700 miles

from military action. The order of evacuation of

the sick and wounded followed an established

protocol. Five echelons of care determined the

disposition of the individual soldier. The

exigencies of combat in Vietnam dictated this

evacuation process. Military medical facilities

varied in distance from the combat zone. The

nearest U.S. logistical support base was in

Okinawa, ca. 1,800 miles from Saigon. I would

serve a short TDY (temporary tour of duty) stint

in Okinawa during my tour of duty. The nearest

complete hospital centers from Saigon were in

Japan, 2,700 miles distant. Travis Air Force Base

in California was 7,800 miles away and Andrews Air

Force Base outside of Washington D.C. was ca.

9,000 miles away. We would be caring for young

soldiers. One major difference between practicing neurosurgery in the army and in civilian life was that the continuing care I could provide patients in the latter was no longer practicable. Severely wounded soldiers would pass through the five levels of care. I would be working at the fourth level where patients could be treated for as long as sixty days if they could to return to active duty in Vietnam. The men who required longer hospitalizations would be evacuated to hospitals in the United States - the fifth level of care. This five-tier system determined where patients were hospitalized. The first echelon: In the combat zone the Medic would render emergency care and begin evacuation to the forward aid station where a medical officer would continue care and resuscitation if needful while preparing the patient for further evacuation to the second echelon (the division clearing station) or to the third echelon (a definitive treatment center). The second echelon: This is the division clearing station where relatively minor injuries were treated. More complicated injuries received continued resuscitation and initial surgery before continued evacuation to the third echelon, a mobile surgical or evacuation hospital. The third echelon: More definitive surgery was

available here along with full resuscitation. This

third echelon Surgical Hospital would often

receive the seriously wounded directly from the

first echelon, the combat zone itself or the

forward aid station. These seriously wounded would

go directly from the forward aid station to the

surgical hospital as rapidly as practicable. The

Evacuation Hospital would receive not only the

soldiers from the aid station but also those

needing specialty surgery from the second echelon

division clearing station and patients already

operated on at the Surgical Hospital. Medical and

psychiatric patients also came to the Evacuation

Hospital. The fifth echelon: These hospitals were located

in the Continental United States and received the

men and women who were unlikely to return to

continued service in Vietnam. In the combat zone small arms automatic weapons

accounted for about one-third of the injuries and

fragmentation missiles, most often from booby

traps, comprised the majority of the others.

Most of the men who reached us at the 249th

hospital had been thus injured. The pattern of evacuating the wounded by ground

that had served in so many previous conflicts was

not practicable in Vietnam. Distances and

hostile terrain necessitated aeromedical support

on a scale not before realized. Prompt evacuation of the wounded from the

battlefield saved many lives that would otherwise

be lost. The use of the helicopters that had

provided rapid air evacuation on a large scale in

the Korean Conflict in the early 1950's was

essential in Nam. It was now possible for a

casualty in Viet Nam to have extensive life-saving

surgery within an hour of being wounded in the

field. An advantage of air transport was that it

was often possible for a wounded soldier to be

flown directly to the unit best equipped to care

for him, whether that was in the first, second or

third echelon. During my tour of duty the number of army

hospitals in Vietnam increased to twenty-three

with five thousand, two hundred and eighty-three

beds. In Cam Ranh Bay the 6th Convalescent

Center provided care for men who would be

sufficiently fit to return to active duty within

thirty days. Our patients reached us from South Vietnam in stages and by progressively smaller transports. The longest leg of the trip was in C-141 planes especially outfitted to accommodate not only the most seriously injured but also those who might be able to return to Vietnam within sixty days. The C-141s landed at Yakota Air Base and then helicopters would transfer the most severely injured soldiers while buses and ambulances would transport the less critically wounded to the general hospitals.

When I arrived in Japan there were some hectic days of settling in, meeting the hospital commander and getting acquainted with the hospital facilities and staff, especially those medics, nurses and doctors with whom I'd be working on the two neurosurgical wards. Before assuming my responsibilities on the neurosurgical unit I retrieved and registered my station wagon that had reached the depot in Yokohama and then arranged with a local broker to rent a house that I felt could accommodate my young family for our anticipated stay of two years. The house was some distance from the hospital - a commute of one and one -half hours on the congested Tokyo roads but only a few blocks from the bus stop where a commuter bus from the American School in Japan would pick up and deliver our two school age children. It would be one month before my family's arrival

in Japan. By then I was settled into the hospital

routine and was immersed in the challenges of

caring for the quantity and variety of injured

soldiers who had reached the fourth echelon of

care at our hospital. My reading in anticipation of military service had raised some strong feelings about our role in the conflict in Southeast Asia and it did not take long for me to feel that we were sacrificing brave young men in an ill-advised adventure far from our own shores. As I made rounds on our wards, treated the continuing stream of casualties that passed through our operating rooms and pronounced dead so many soldiers who had been grievously wounded in combat I resolved to do what I could do to end the carnage. I was enough of a realist to know that while I was on active duty there was nothing I could do but strive to do the very best that training and experience had taught me. I would treat, comfort and whenever possible restore to some semblance of well-being those who came under my care. However, I knew my own tour of duty in the army would last for only the mandatory two years, and if the war had not ended when I was discharged then I would do what I could to help end it. How I would do that I did not know, but I did know that it must end. [From Washington Post - 04/30/2017: Early on I purchased at the Tachikawa Airbase PX a 35 millimeter Nikon FTN camera that I kept close at hand and recorded much of what I experienced both on and off base. Towards the end of my tour I gave a slide presentation of my impressions and thoughts to my colleagues at a Grand Rounds session. Choosing which slides to show from the hundreds that I had by then accumulated was difficult. There were no objections to the efforts of myself and those who wanted to see an end to our involvement in Nam but the highest ranking attendee, a career colonel, adamantly refused to join the post-presentation discussion of what he considered to be a political issue.

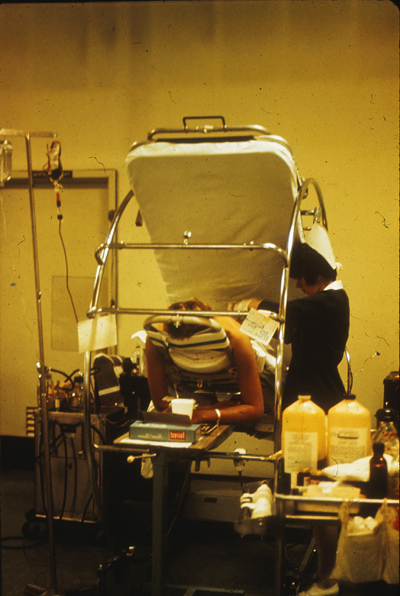

A partial view of our ward with trapeze and safety rails on almost all beds.

Nurse and physician caring for a paraplegic patient on a Stryker frame, enabling the patient to be rotated 180 degrees frequently in order to prevent skin breakdown and the formation of bed sores.

View of patients in beds with safety rails and CircOlectric beds in background.

A nurse caring for a paraplegic patient on a CircOlectric bed.

Two nurses with recovering patient.

Two general surgeons consulting on one of our patients.

In the neurosurgical operating room. The 249th General Hospital was not so very

different from the major hospitals where I had

received my general and neurosurgical training in

the States. Both health professional draftees and

career army officers represented the various

specialties. The medical staff consisted of

captains, majors and colonels with the rank

determined by degree of training and experience.

The nurses who were the closest to the continuing

oversight and care of the patients were drawn from

both military and civilian lives. Assignments of

the doctors on the neurosurgical wards overlapped

so that there was sufficient time for the outgoing

surgeons to orient the newcomers to the individual

patients and their clinical situations. Our two

wards at the 249th had two fully trained

neurosurgeons and two medical officers attending

the patients throughout my tour. The chief of

service was a major who would be promoted to

lieutenant colonel during the tour, and I began

with the rank of captain to be promoted to major.

Two captains completed the physicians' staffing on

our unit. The military nursing staff on our wards

contained lieutenants and captains. There were

also a number of civilian nurses, spouses of

active duty military personnel who were stationed

in Japan. The medics varied in rank. The

census on our wards during most of my tour varied

between sixty and eighty patients. The pace and stress accompanying our workload varied with the progress of hostilities in Vietnam as most of our days and nights were centered on the tasks at hand. We concentrated on admitting and evaluating patients as they arrived at the hospital from the C-141 transport planes that had evacuated them from Nam. Our assignment was to provide continued surgical treatment in our operating rooms, and then prepare them for further evacuation back to the States or, in fewer cases, back to active duty in Southeast Asia. It was years later when I could correlate the conditions that obtained in the combat zones with what we were witnessing in our hospital. It was not until 1972, three years after my tour of duty, that I went to work in Vietnam and saw first hand some of the results of our intervention.. The soldiers who reached our hospital presented many of the same challenges that I had encountered and treated in civilian life but the extent, variety and devastation of injuries far exceeded what I had encountered in my previous years of residency and practice. We were not the first neurosurgeons to care for our patients. The majority of soldiers whom we treated after evacuation from Southeast Asia had injuries that required additional cranial or spinal surgery before continued transport to the continental United States. Rarely would these men be returning to active duty in Nam. Now and then we could chuckle at our circumstances and those of our patients. One such event was the evacuation from South Vietnam of a soldier who had no injury but had gone through induction, training and deployment to Vietnam despite lacking a significant portion of his skull. One quarter of the bony protection of his skull had been removed following an adolescent injury and this had never been replaced. The scalp was well healed and he was in fine physical shape, but the skull defect and the underlying pulsating brain were prominent. The private enjoyed a few weeks of unanticipated rest and relaxation after the replacement of the defect with a methylmethacrylate plate insertion. Then he was back to fight another day. During my tour of duty military actions in Nam and events at home occurred that were to influence the course of the hostilities and eventually the departure of our own troops from South Vietnam. At the end of 1967 American troops in country numbered 485,600. Total deaths of U.S. troops in the "Vietnam War" had reached 19,562. General Westmoreland had started to fortify Khe Sanh, the linchpin of the contemplated electronic barrier monitoring infiltration from the north. Anti-war protests were escalating at home. Our workload at the hospital followed a routine - regular arrivals from the airbases, helicopter or ambulance transfer to our wards, triage, evaluation, observation, pre-operative treatment, surgery as needed, post-operative care and preparation for continued evacuation to the continental United States or occasionally back to the combat zone. The years of 1967 and 1968 were pivotal as events unfolded both at home and in Vietnam. Although what was happening on the "home front" had little impact on our daily activities the battles in Nam did. On October 21, 1967 there was a march on the Pentagon that brought out 100,000 antiwar protesters. In November there were heavy casualties in fighting around Dak To in the Central Highlands. That same month the Secretary of Defense, Robert McNamara, who was having misgivings about our involvement, resigned. A day later Senator Eugene McCarthy, who had long opposed the war, began a challenge to President Johnson for the presidential nomination in 1968. Anti-war protests increased. The Tet Offensive began on January 31, 1968. Our workload had been steady and heavy up to Tet

when it increased with the escalation of

hostilities. Each year from 1965 had brought

greater numbers of army patients evacuated from

Vietnam. Belatedly, but happily, after 1969 a gradual

de-escalation of our nation's combat role in

Vietnam began. Before then General Westmoreland had requested 206,000 more troops. Clark Clifford, who had succeeded the unhappy Robert McNamara as Secretary of Defense advised against this buildup and President Johnson concurred. 1968 was an election year and antiwar protests were increasing. On March 12 in New Hampshire's Democratic primary Eugene McCarthy received 42% of the vote. On March 16 Robert Kennedy announced his candidacy for president. Creighton Abrams replaced Westmoreland in Vietnam and the latter was appointed Army Chief of Staff. We knew about the unrest at home. In early November, 1968 I accompanied a critically ill soldier from the 249th to Walter Reed Hospital. Passing through the streets of Washington I saw the lingering results of the rioting and destruction that had followed Martin Luther King's assassination in April. One thousand, one hundred, ninety-nine buildings had been badly damaged or destroyed. Many remained abandoned and boarded up. Over one thousand citizens had been injured. Twelve had been killed. To combat the unrest and looting the White House had dispatched some 13,600 federal troops. That occupation of Washington was the largest of any American city since the Civil War. How ironic that our marines had deployed machine guns on the steps of the capitol while their comrades in arms were fighting for their lives halfway across the world! In Japan the census in the medical and surgical services remained high. The flow of head, spine and peripheral nerve injuries continued. Many of the spinal injuries we encountered brought new experiences. I had previously operated up and down the spine in what were textbook situations: disc disease, fractures of the vertebral column, tumors, neonatal deformities, vascular anomalies, degenerative disease, but our patients returning from combat presented new and unique challenges. Closed wounds of the spine were less frequent than open ones. The former usually resulted from helicopter crashes or explosions below vehicles. The latter, caused by penetrating missiles, were more common and more complicated because of associated injuries to other parts of the body. In the combat zone life-threatening wounds frequently mandated the treatment of associated chest or abdominal trauma that took precedence over surgical intervention at the spinal column. When many such patients reached us the medical and surgical hurdles were unique. Some patients who had lost movement and sensation in their lower bodies arrived with extensive breakdown of their skin and muscle below the site of injury. These pressure or decubitus ulcers were often infected and required removal of gangrenous tissue, frequent cleansing, Betadine (povidone-iodine) applications and dressing changes. Skin grafts or flaps were necessary in many of the more extensive wounds and further surgical procedures would often be deferred until evacuation back to the States.

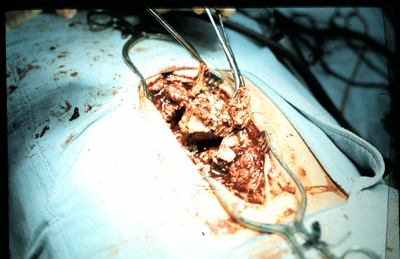

Necrotic decubitus ulcer

Deep wound of low back

Removing infected vertebral body from soldier's back

Necrotic vertebral body now freed from back and surrounding infected site

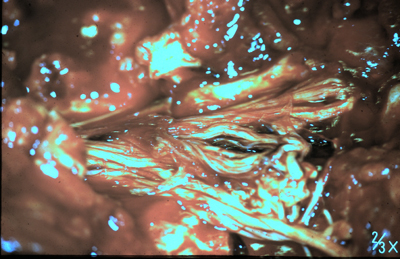

Exposed spinal nerves and nerve roots of the

cauda equina (Latin for "horse's tail") in an open

low back wound As previously noted The Vietnam Veterans Memorial

Wall in 2018 listed 58,320 names. The names of the

3 million Vietnamese who perished in the conflict

have no such wall, but as Philip Jones Griffiths,

the renowned photographer of the conflict,

observed, The causes of wounds in Vietnam reflected the increased use of small arms and automatic weapons contrasted with the earlier experiences of World War II and the Korean Conflict. In these earlier engagements about 75 per cent of all wounds were attributed to missile fragment wounds from artillery, mortar and aerial bombs. In Vietnam such missile wounds made up 49.6 per cent of injuries while gunshot wounds made up 42.7 per cent (Military Surgical Practices of the United States Army in Viet Nam, Medical Field Service School, Brooke Army Medical Center, Fort Sam Houston, Texas, 1966 by Yearbook Medical Publishers, Inc.).

Soldier with multiple fragment wounds of back and buttock

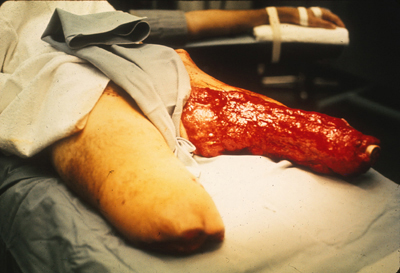

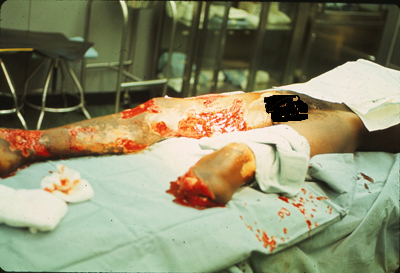

Bilateral lower limb injuries necessitating further revision of amputation stumps

Leg amputation

Multiple fragment wounds with loss of right lower leg

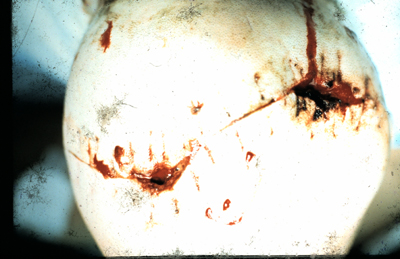

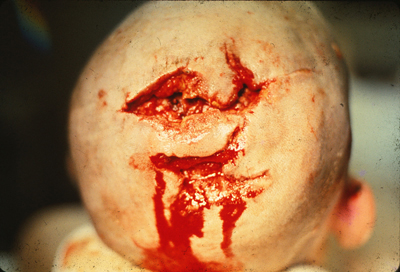

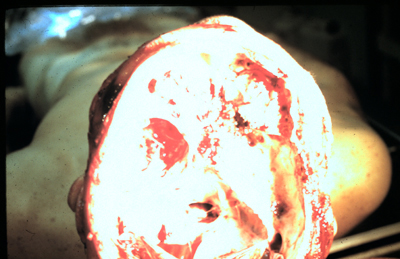

Gunshot wound to head with breakdown of scalp closure

Scalp breakdown following debridement of infected

entry sites over

Death after uncontrollable generalized infection of brain

Disruption of base of skull after devastating facial and sinus missile injury On January 30, 1968 the Viet Cong and North

Vietnamese began the Tet Offensive and the next

few weeks were the busiest of my tour of duty.

During the second week in February the 543

Americans killed in action marked the highest

weekly total of the war. The soldiers had the

support of 116 air ambulance detachments.

Five to seven Huey helicopters were assigned to

each detachment and they could carry six to nine

casualties on one flight. On Thirty-nine crew members were killed and two

hundred-ten were wounded in a two-year period as

they flew rescue missions [Neel, page 73].

The number of flights increased in proportion to

our escalating involvement. 1965 - 13,004,

1966 - 76,910, 1967 - 85,804, and in 1969 -

206,229 [Neel - page 75]. In 1969

hoist retrievals of casualties by dust-off

helicopters rescued 2,516 patients [Neel - page

75]. As the numbers of wounded reaching our hospital escalated my determination to do whatever I could to protest the enormity of the conflict became an obsession. I had to wait until September, 1969. In contrast to the hospital environment and ongoing care of casualties life away from the base provided a welcome respite. Our home for the overseas years was a classic Japanese house, a wooden structure of two stories and much like what I had come to expect from my preparatory reading in anticipation of the move. With the help of colleagues at the hospital I had found live-in help, a young woman who had a fair command of English and whom I hoped would make the transition for my family as easy as possible.

My wife, four children and one beagle arrived in

mid-October and I introduced them to what would be

somewhat less than two years in this country. I

would likely be at home even less than when I had

been in private practice. In Framingham I lived

within fifteen minutes of my office and hospital.

The longer commute and the responsibilities of

treating wartime casualties would likely result in

my having not much time at home. I was thinking

that the relatively comfortable and somewhat

exotic living arrangements, the presence of

live-in help and the opportunity for the older

children to attend school with a group of

international students would help in this

transition. There would certainly be new

experiences. Living in a home with movable Shoji

screens for walls, tatami mats for flooring,

sleeping on futons that would be folded for

storage each morning. The wooden components of the

house were Japanese cypress. The fenced-in garden

allowed a safe place for the children to play and

our beagle Tammy to run. Our full-sized Ford

station wagon could fit in a detached garage that

was constructed of sturdy plastic walls and a

corrugated roof. One of the many novelties was the

deep cedar tub that afforded us the unique

Japanese bathing ritual. Food stalls and shops

were less than one hundred yards down the street

as was the local railroad station with direct

service to downtown Tokyo. 218 Karasuyama,

Setagaya-ku was to be our home for most of the

next two years. Directly across the street from our home was a

Shinto shrine. During comparatively "quiet"

periods at the hospital we were able to visit

sundry Shinto shrines and Buddhist temples while

exploring further afield. The majority of my days was spent at the hospital but there were also opportunities to take advantage of free hours and vacation days to explore some of the attractions of not only Tokyo but also of other parts of the country. It was a long two years and much of my work was necessarily heart-wrenching. The respite from the hospital activities was welcome and there was much to see and value about this country that I would never had had the opportunity to appreciate were it not for the ongoing hostilities in Nam. Needless to say, I would have gladly forgone the adventures of traveling in this land had there been no conflict responsible for bringing us here. Temples in Kyoto:

Cherry blossoms in Ueno Park:

During the same period that we were working in Japan the conflict and military activities in Nam itself occupied most of the news. Much of what was happening during that time I learned only after retiring from active duty. Journal articles and books appeared with increasing frequency as we slowly reduced our commitment to the South Vietnamese government. General Westmoreland assigned Major General Spurgeon Neel the task of preparing a monograph of the army's medical activities in Vietnam for the years 1965-1970. It was from this monograph, Medical Support of the U.S. Army in Vietnam, 1965-1970, that I came to more clearly understand the challenges that faced our troops and the physicians tasked with their care in the combat zone during those years. After leaving active duty in 1969 I returned to

the practice of civilian neurosurgery in

Massachusetts, but I continued to closely follow

the news from SouthEast Asia and became

increasingly active in opposing our continued

military activities in Vietnam. I presented my

impressions and slide presentations on TV stations

in Boston, New York and Baltimore and college

campuses both locally and as distant as Kansas

City, Missouri. On December 7, 1970, thirty-nine

years after "a date which will live in infamy" the

University Program Council Lecture Committee at

The University of Missouri-Kansas City sponsored

my slide presentation. The campus magazine quoted

one of the more telling points of this talk, the

fact that had continued to disturb me as the

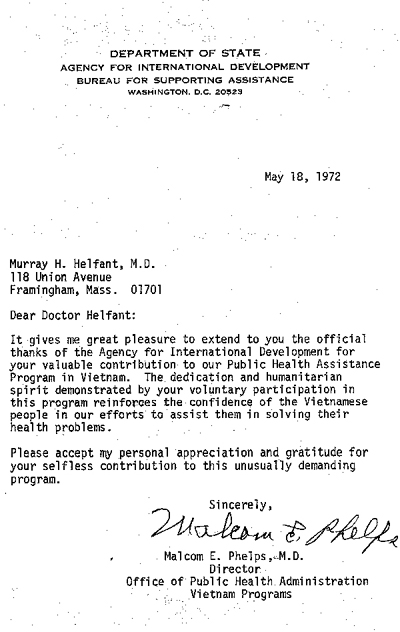

hostilities continued: I shared a platform with Ramsey Clark in Chicago at a meeting of Business Executives Move for Vietnam Peace. I presented facts and figures to colleagues at meetings of The Massachusetts Medical Society and the New England Neurosurgical Society. By the end of 1971 56,205 U.S. troops had been killed in the Vietnam War. In our country opposition to the war continued. On March 23rd of 1972 the United States suspended the Peace Talks in Paris, and a week later the North Vietnamese began a new offensive, the heaviest since 1968. The next month saw the initiation of Operation Linebacker, expanding air strikes against the North Vietnamese fighters in South Vietnam. During these same months, sponsored by the Agency for International Development of the Department of State, I was in Vietnam. I had traveled to South Vietnam to see for myself not only the results of our ongoing intervention in country but also the conditions under which medical teams tried to deliver care to the large numbers of sick and wounded. I worked primarily in Saigon as a Visiting Neurosurgeon at the Cho Ray Hospital and Lecturer in Neurosurgery at the medical school, but was also able to travel further afield to military and civilian medical facilities in Pleiku, Kontum and Nha Trang.

Scenes from The Cho Ray Hospital in Saigon - the

unit in which I spent the most of my time.

Patients lining the corridors waiting to be seen

Three infants - one crib

A representative ward

Two nursing instructors

Nurses and student nurses - 1 Nurses and student nurses - 2

Child with scalp wound

Child recovering from head wound Wound care

Conference and review of skull x-rays

Operating room

Operating room during cranial surgery; overhead

lights provided by

Contrasting technologies - from a state of the

art operating room to

Entrance to military hospital

Grounds of the Cong Hoa army hospital in Saigon

Audience of army doctors as we discuss neurosurgical challenges in wartime

Entrance to children's hospital Outside the hospital I spent as much time as I

could exploring Saigon, visiting the orphanages

and schools, photographing street scenes and

contrasting how removed from life in the hospitals

and rehabilitation units were the everyday

activities in the capital city. Striking were the

smiles and cheerfulness of the children,

especially the younger ones.

A few pictures from Kontum in the Central Highlands:

Performing a lumbar puncture while Montagnard

tribesmen observe

|